近日,科学家发现了一种可以将像普通开关一样随意开启和关闭的方法。科学家们复制出与记忆相关的神经信号发放,设计出一个电子信息系统,能够在大鼠体内模仿与长期记忆相关的脑部功能,甚至是当大鼠服用导致失忆的药物后该系统也同样有效。

“开关打开,然后大鼠就恢复记忆;开关关闭,大鼠就丢失记忆。” 来自南加州大学维特比工学院(USC Viterbi School of Engineering)工程系生物医药工程的西奥多·柏格(Theodore Berger)教授如是说。柏格是近期发表在《神经工程期刊》(Journal of Neural Engineering ) 一篇文章的第一作者。他的团队与来自维克森林大学(Wake Forest University)的科学家一起完成了这项基于之前人们对于海马及其在学习行为中的功能而进行的研究。

在这项研究中,实验人员先让大鼠进行学习训练,按某一个按钮即可以获得特定的奖赏。由维克森林大学心理及药理系的塞缪尔·戴德威勒(Sam A. Deadwyler)教授领队,科学家们运用植入式的电极探针记录了大鼠大脑海马内部两个主要分区之间的活动,这两个亚区被称为CA3和CA1。该团队的前期研究显示,在大鼠的学习过程中,海马会将短期记忆转化为长期记忆。

“大鼠没有了海马,”柏格认为,“就没有长期记忆,但短期记忆仍然会存在。” 先前的研究结果认为是CA3和CA1互相作用从而产生了长期记忆。令人吃惊的是,实验人员用神经阻滞药物将负责该项功能的两个区域的联接阻断后,之前训练过的大鼠忘记了经过长期记忆学会的行为。柏格表示,“这部分大鼠仍然表现它们还记得‘当你按下左键然后按下右键,然后再颠倒顺序’这个过程,并且它们大部分仍然知道按键意味着有水喝,但是他们只能在5-10秒钟之内记得刚才按过的是左键还是右键。”

由柏格教授领队的修复学研究团队建立了一个模型,并且将该实验结果继续深入,人工合成出了一种海马系统。该系统可以模拟出CA3-CA1的相互作用模式。当这个团队将电极设备模拟记忆编码功能时,被药物阻滞记忆的大鼠恢复了长期记忆的能力。另外,这些研究者们进一步探索了如果将此修复设备以及与其连接的电极植入具有完整功能海马的动物中,这个设备可以对大脑内部记忆形成进行强化,并且增强动物的记忆能力。

该研究团队的文章中写道,“这些植入的实验模型研究头一次证明了,有了足够多的关于记忆的神经编码信息,能够识别和增强实时记忆的神经模拟系统能恢复甚至强化认知记忆过程。”

根据柏格和戴德威勒的说法,下一步他们尝试在灵长类动物(例如猴子)中实施该项实验,最终目的是力图开发出能够帮助患有阿尔兹海默症,中风或者后复建的人类的相关设备。

来源:sciencedaily 6月17日

米兰1.0 编译,renard 审稿

============================================================

这研究太给力了,不得不转。bio工程学的同僚们太伟大了!

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110617081543.htm

原文:http://iopscience.iop.org/1741-2552/8/4/046017/pdf/1741-2552_8_4_046017.pdf

ScienceDaily (June 17, 2011) — Scientists have developed a way to turn memories on and off -- literally with the flip of a switch. Using an electronic system that duplicates the neural signals associated with , they managed to replicate the brain function in rats associated with long-term learned behavior, even when the rats had been drugged to forget.

"Flip the switch on, and the rats remember. Flip it off, and the rats forget," said Theodore Berger of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering's Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Berger is the lead author of an article that will be published in the Journal of Neural Engineering. His team worked with scientists from Wake Forest University in the study, building on recent advances in our understanding of the brain area known as the hippocampus and its role in learning.

In the experiment, the researchers had rats learn a task, pressing one lever rather than another to receive a reward. Using embedded electrical probes, the experimental research team, led by Sam A. Deadwyler of the Wake Forest Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, recorded changes in the rat's brain activity between the two major internal divisions of the hippocampus, known as subregions CA3 and CA1. During the learning process, the hippocampus converts short-term memory into long-term memory, the researchers prior work has shown.

"No hippocampus," says Berger, "no long-term memory, but still short-term memory." CA3 and CA1 interact to create long-term memory, prior research has shown.

In a dramatic demonstration, the experimenters blocked the normal neural interactions between the two areas using pharmacological agents. The previously trained rats then no longer displayed the long-term learned behavior.

"The rats still showed that they knew 'when you press left first, then press right next time, and vice-versa,'" Berger said. "And they still knew in general to press levers for water, but they could only remember whether they had pressed left or right for 5-10 seconds."

Using a model created by the prosthetics research team led by Berger, the teams then went further and developed an artificial hippocampal system that could duplicate the pattern of interaction between CA3-CA1 interactions.

Long-term memory capability returned to the pharmacologically blocked rats when the team activated the electronic device programmed to duplicate the memory-encoding function.

In addition, the researchers went on to show that if a prosthetic device and its associated electrodes were implanted in animals with a normal, functioning hippocampus, the device could actually strengthen the memory being generated internally in the brain and enhance the memory capability of normal rats.

"These integrated experimental modeling studies show for the first time that with sufficient information about the neural coding of memories, a neural prosthesis capable of real-time identification and manipulation of the encoding process can restore and even enhance cognitive mnemonic processes," says the paper.

Next steps, according to Berger and Deadwyler, will be attempts to duplicate the rat results in primates (monkeys), with the aim of eventually creating prostheses that might help the human victims of Alzheimer's disease, stroke or injury recover function.

The paper is entitled "A Cortical Neural Prosthesis for Restoring and Enhancing Memory." Besides Deadwyler and Berger, the other authors are, from USC, BME Professor Vasilis Z. Marmarelis and Research Assistant Professor Dong Song, and from Wake Forest, Associate Professor Robert E. Hampson and Post-Doctoral Fellow Anushka Goonawardena.

Berger, who holds the David Packard Chair in Engineering, is the Director of the USC Center for Neural Engineering, Associate Director of the National Science Foundation Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems Engineering Research Center, and a Fellow of the IEEE, the AAAS, and the AIMBE

"A Cortical Neural Prosthesis for Restoring and Enhancing Memory." (Berger et al 2011 J. Neural Eng. 8 046017)

摘录下原文里重要信息:

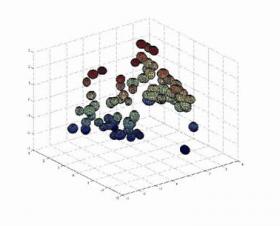

[Abstract] A primary objective in developing a neural prosthesis is to replace neural circuitry in the brain that no longer functions appropriately. Such a goal requires artificial reconstruction of neuron-to-neuron connections in a way that can be recognized by the remaining normal circuitry, and that promotes appropriate interaction. In this study, the application of a specially designed neural prosthesis using a multi-input/multi-output (MIMO) nonlinear model is demonstrated by using trains of electrical stimulation pulses to substitute for MIMO model derived ensemble firing patterns. Ensembles of CA3 and CA1 hippocampal neurons, recorded from rats performing a delayed-nonmatch-to-sample (DNMS) memory task, exhibited successful encoding of trial-specific sample lever information in the form of different spatiotemporal firing patterns. MIMO patterns, identified online and in real-time, were employed within a closed-loop behavioral paradigm. Results showed that the model was able to predict successful performance on the same trial. Also, MIMO model-derived patterns, delivered as electrical stimulation to the same electrodes, improved performance under normal testing conditions and, more importantly, were capable of recovering performance when delivered to animals with ensemble hippocampal activity compromised by pharmacologic blockade of synaptic transmission. These integrated experimental-modeling studies show for the first time that, with sufficient information about the neural coding of memories, a neural prosthesis capable of real-time diagnosis and manipulation of the encoding process can restore and even enhance cognitive, mnemonic processes.