By GEORGE STADE

Erik Erikson's new book, an amplified version of his Jefferson Lectures of 1973, is not so much an argument as a series of preparatory hems, transitions, digressions, excurses and recapitulations in search of an argument. Had he found it, were it not always just appearing around the curve of his psychohistorical and psychoanalytic thought, it might have turned out to be about "this once-in-history chance for self-made newness" that was and is "the singular significance of the phenomenon of the United States."

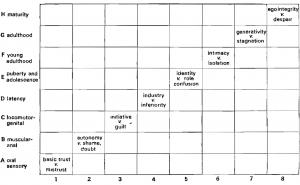

As it is, keeps bumping into the multiform aspect of Thomas Jefferson, who as the representative case among "the founding personalities in the emergence of a new identity" has left his monuments at every turn. The paths around Jefferson unwind "from case history to history," from "the inner economy of a person" to "the whole ecology of greatness." We arrive finally at the vista that reveals how "the inner economy of single person is really (or also) an ecology of interrelations" -- with a particular historical situation, a local epistemological set, a concrete social scene. We are what we see, where we see it, and with whom.

There are stopovers for glance at Monticello, which Jefferson crowned "with an octagonal dome, thus adding an equally dominant maternal element to the strong facade." There is an introduction to Maria Cosway, who seems, says Erikson, to have served as Jefferson's "Anima." There are quick peeps this way and that through psychoanalytic lenses a "the American work ethos, the surest antidote against primal guilt," at the protean quality of the American personality, at the astounding and fascinating consequences of "the phylogenetic given of mans' verticality," of his having a top and bottom, a front and back, a right and left, at the "ontogeny of conscience in the generational succession of life cycles," and, finally, at the liberation movements of "the Black, the young, and the female."

The interactions of these last with the society at large expose "the relation of inner repression to outer suppression." One attributes to the Other -- whether racial, generational, or sexual -- what one considers undesirable in oneself; to put down the one feels like putting down the other. "The positive identity," that is, "must ever fortify itself by drawing the line against undesirables, even as it must mark itself off against those negative potentials which each man must confine and repress, deny and expel, brand and torture, within himself." This, I might add, is the lesson of the movie "Dr. Strangelove," and it is the lesson, as Erikson points out, of the recent shenanigans in Washington. "There is no woman in the whole, long Watergate line-up," he says, forgetting Rose Mary Woods, but there is certainly no black or ex-student radical, no radical of any kind for that matter, scarcely a liberal even.

The terminal point of Erikson's divagations is that "liberation can only come from historical insight, including that regarding the use and misuse of guilt in politics." The point is unexceptional, but familiar, like most of the conclusions in this book, and like the conclusion toward which Nobel prize-winning ethologist Konrad Lorenz works in his new book: "we must learn to combine judicious understanding of the individual with consideration for the rights of the community." The past that Lorenz feels we must know (before judicious understanding can prevail) is not historic, but prehistoric. We must become aware, he insists, of the presence within us of our phylogenetic past.

The eight deadly sins of his title are the consequences of what were once virtues bred into us by evolution. They were bred into us during the millions of years before civilization, when we were parts of the natural settings we were in. All the constituents of such a setting -- plants, animals, minerals, climate and topography -- for a system in which "everything is linked to everything else by causal inter-action." Animals, including the human animal, are linked to the other constituents of such systems by behavioral and emotional dispositions as well as by the shapes of their bodies.

Animals, that is, have "behavior programs of phylogenetic origin," dispositions to do and feel this and that according to the history of their interactions with everything around them, including each other. These adaptive dispositions are virtues in the hedonistic sense: they promote the well-being of the species that have them. When you are in a natural setting, you naturally look, feel, and do right, to others and yourself.

But we are no longer in a natural setting of technology and rapid social change we are now in has turned our cultural wisdom into foolishness, our phylogenetic knowledge into ignorance of what to do or feel, our evolutionary virtues into eight deadly sins.

These are: 1) overpopulations, which turns a society into a behavioral sink and reinforces the other sins; 2) the devastation of the natural environment, with consequent atrophy of our esthetic and ethical feelings; 3) "man's race against himself," or a ruthless "intraspecific" competitiveness, which in the absence of effective "extra-specific" influences, "works in direct opposition to all the forces of nature, destroying all the values they have created" ("specific" is the adjective derived from "species").

Then: 4) an entropy of feeling, an increased sensitiveness to unpleasurable experience combined with a decreased capacity for pleasure and a childish insistence of instant gratification; 5) genetic decay, the loss through domestication, through the loss of extraspecific selecting pressures, of "all delicately differentiated behavior patterns of courtship and pair formation" an of our natural sense of justice; 6) the break with tradition, with culture, a body of adaptive knowledge that "has grown by selection in the same way as it develops in an animal species" and that is just as hard to begin from scratch as a new species of animal; plus the consequent conflict between generations; 7) the easy indoctrinability of modern man, especially by behaviorist ideology -- "the present-day rulers of America, China and the Soviet Union are unanimous in one opinion: that unlimited conditionality of man is highly desirable." And finally 8) a willingness, resulting from the first seven sins, to manufacture and use nuclear weapons.

What makes all this unconvincing, of course, is the distance between the ethology and the sociology. Lorenz may be right or wrong about the survival in us of residual dispositions that were once adaptive. He is surely right that industrial societies suffer from at least eight sins, whether or nor the year exactly the ones he enumerates. But he has not been able to fit together in any precise or concrete way the relations among our dispositions, our sins, and our newfangled technological environment.

Worse, while the ethology we are given often is sophisticated and interesting, especially in the illustrative data and supporting evidence, the sociology is naive, muddled, and founded mostly on rumor. Lorenz confuses causes with consequences, institutions with fashions, secondary effects with world-historical convulsions, his own prejudices with natural law. His notion of serious sociology is the kind of thing you get from Vance Packard and Philip Wylie.

Neither of these books, in short, satisfies entirely, although each has its virtues. Together they make us step back to a perspective from which we might see "the epidemic mental illness afflicting present-day humanity" (to quote the ethologist) as a function of "our common evolutionary corruptibility" (to quote the psychologist). Whatever the holes in Lorenz's argument, it seems plausible to me that evolution has built into us irreducible dispositions and needs and that these fuel the resentment against any social order that does not satisfy them. And whatever the inconclusiveness of Erikson's meanders, it is good to be in his company, good to follow his sane, humane and wry musings on the crooked byways of our national character.

George Stade is chairman of the English department at Columbia College.

DIMENSIONS OF A NEW IDENTITY

By Erik H. Erikson

CIVILIZED MAN'S EIGHT DEADLY SINS

By Konrad Lorenz