By PAUL VITELLO

Published: June 4, 2011

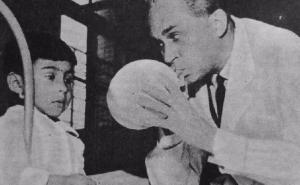

Dr. Leo Rangell, a leading during the heyday of classical Freudian talk therapy in the 1960s and ’70s, and a relentless advocate for the slow approach to treating distress even asand managed care made short-term treatment the norm, died on May 28 in Los Angeles. He was 97.

Dr. Leo Rangell, a leading during the heyday of classical Freudian talk therapy in the 1960s and ’70s, and a relentless advocate for the slow approach to treating distress even asand managed care made short-term treatment the norm, died on May 28 in Los Angeles. He was 97.

His family said the cause was complications of a surgical procedure the day before at the U.C.L.A. Medical Center.

Dr. Rangell, a practicing psychoanalyst and emeritus clinical professor ofat the Los Angeles and San Francisco campuses of the University of California, remained active until the end of his life — teaching, writing for scholarly journals, seeing patients until a few days before he died and.

His stamina as a writer and teacher, and as a major player in the often contentious political world of the psychoanalytic profession, was legendary. He published 450 academic papers during his lifetime and nine books, the last at the age of 94. Dr. Rangell’s prominence in his field coincided with a sea change in American attitudes about psychological treatment during the late 1960s.

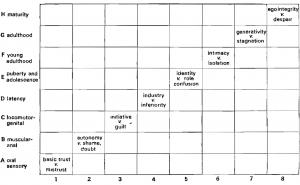

The emerging availability of psychoactive prescription drugs, as well as competition from, social workers and even New Age practitioners, began to diminish the appeal of classic psychoanalytic treatment, with its arduous exploration of unconscious feelings in sessions two or three times a week that could span years.

In an interview with The New York Times in 1968, Dr. Rangell acknowledged the changes in the air but attributed them to a kind of cultural misunderstanding. In the can-do, post-World II American imagination, he said, psychoanalysis had become wrongly perceived as a cure-all.

“The hopes of the general public exceeded all reasonable expectation,” he said. “There were hopes that a generation of children could be brought up free of problems, that psychoanalytic insight would rid the world of crime, divorce and learning problems. Now there’s a big letdown.”

Throughout the subsequent decades, as new forms of therapy continued to multiply — and managed care insurance limitedcoverage for many people — Dr. Rangell remained an advocate for the fundamental insights laid down by Sigmund at the beginning of the 20th century.

“There are always fashions and fads and pendulum swings,” Dr. Rangell said, “but no explanatory system of human behavior has as yet supplanted the psychoanalytic one.”

Peter Loewenberg, a psychoanalyst and professor of the history of psychoanalysis at U.C.L.A., described Dr. Rangell as one of the profession’s “leading statesmen” and a voice for humanistic values in an age of quick-fix therapy.

“Everyone today is led to believe that they will feel better if they take a pill, and that is sometimes true,” Dr. Loewenberg said. “What Leo Rangell promoted was the analytical tradition of understanding the self.”

Dr. Rangell’s books included several that explored issues of ethics and responsibility from unique perspectives. His 1980 book, “The Mind of Watergate: An Exploration of the Compromise of Integrity,” focused on the psychological mechanics of what he said was the American public’s tendency to be “gullible or easily seduced, and susceptible to leaders of questionable character.” In 1989, in “The Human Core,” he wrote about the meaning of free will in the context of Freud’s idea of the “unconscious,” which he identified as the engine of all behavior.

In his final book, “The Road to Unity in Psychoanalytic Theory,” Dr. Rangell proposed what some in the historically factious psychoanalytical world considered quixotic: a reconciliation of all the branches — Adlerian, Sullivanian, Kleinian, Kohutian, Reichian, et al. — under one Freudian roof. His “unitary psychoanalysis” would clear up public confusion and might restore confidence in the psychoanalytic method, he said.

“Is it acceptable that a patient should turn out to have an ‘Oedipal conflict’ or a problem with ‘self-cohesion’ depending on which analyst he is with?” he wrote in 2007, at age 94.

Dr. George Makari, an associate professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, said Dr. Rangell’s challenge underlined the endurance of his passion for the psychoanalytic tradition.

“Whether you agree with his opinion about the proper answer or not, that is a very important question,” Dr. Makari said. “He articulated a problem that has been with us for a long time.”

Leo Rangell was born on Oct. 1, 1913, in Brooklyn, the oldest of four children of Morris and Pauline Rangell, immigrants from Russia and Poland respectively. He graduated from Boys High School and Columbia University and studied medicine at the University of Chicago, finishing his training in psychiatry and neurology in New York. During World War II, he was an Army psychiatrist, treating former prisoners of war and airmen who had survived plane crashes. He moved to California after the war.

Dr. Rangell’s wife of 58 years, Anita Buchwald Rangell, died in 1997; a son, Richard, also died. He is survived by two daughters, Judith Alley of Berkeley, Calif., and Susan Harris of Boulder, Colo.; a son, Paul, of Santa Cruz, Calif.; and a sister, Sydelle Levitan of New York.

In 1995, while recovering from, Dr. Rangell developed an unusual malady that he subsequently wrote about on The Huffington Post. He began having aural— hearing Hebrew chants, big band standards like “Chattanooga Choo-Choo” and traditional American songs like “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” that no one else heard.

Hisas he called it, alarmed him at first, then gradually became a part of his interior life.

“I have become familiar with a new dimension of me,” he wrote in a 2006 blog post. “The songs come on their own and I listen. I am listening to me.”

www.nmgpsy.com内蒙古心理网